As the global demand for sustainable and cost-effective energy storage solutions intensifies, sodium-ion (Na-ion) batteries have emerged as a compelling alternative to traditional lithium-ion (Li-ion) technologies. With abundant raw materials, lower environmental impact, and promising electrochemical performance, Na-ion batteries are rapidly gaining traction in applications ranging from grid-scale energy storage to electric vehicles and consumer electronics. At the heart of this innovation lies a fundamental electrochemical process: the reversible movement of sodium ions between the cathode and anode during charging and discharging. In this article, we explore the intricate mechanisms that govern the charge and discharge cycles of sodium-ion batteries, shedding light on why this technology is poised to reshape the future of energy storage.

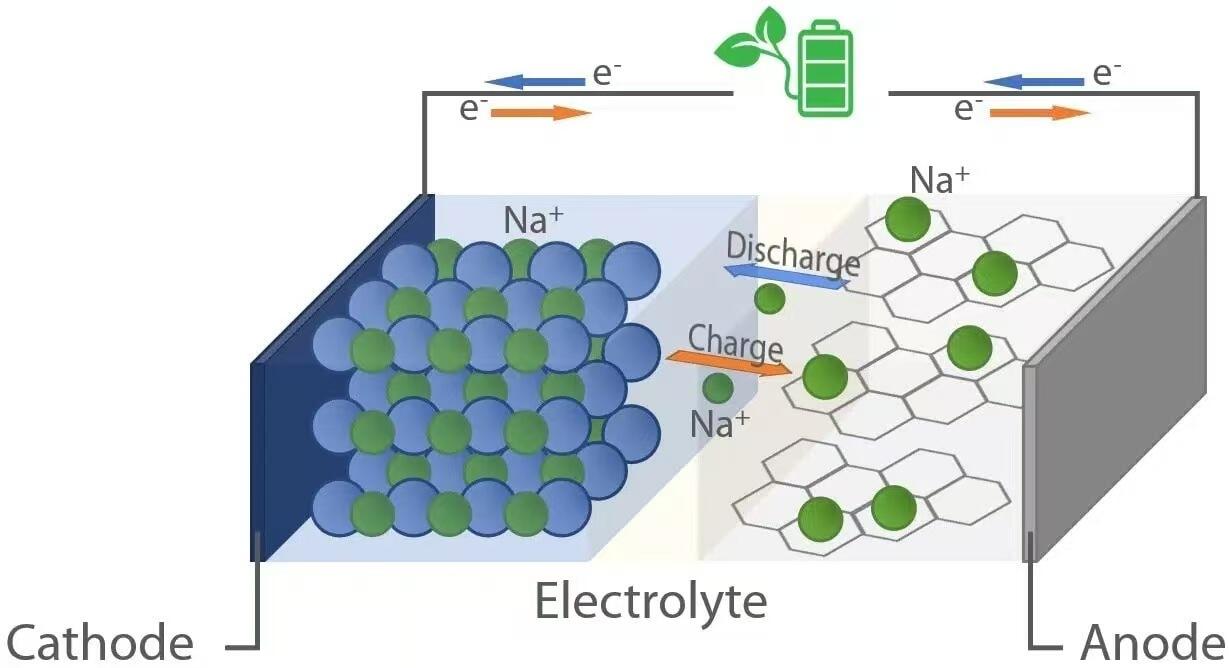

Like their lithium-ion counterparts, sodium-ion batteries operate on the principle of “rocking-chair” electrochemistry. During discharge—when the battery powers a device—sodium ions (Na⁺) migrate from the anode (negative electrode) through the electrolyte to the cathode (positive electrode). Simultaneously, electrons flow through the external circuit, delivering electrical energy to the connected load. Conversely, during charging, an external power source drives sodium ions back from the cathode to the anode, storing energy for future use. This reversible ion shuttling is facilitated by host materials in both electrodes that can reversibly intercalate (insert) and deintercalate (extract) sodium ions without significant structural degradation.

When a sodium-ion battery discharges, oxidation occurs at the anode. Common anode materials include hard carbon, which possesses a disordered structure with nanopores capable of accommodating Na⁺ ions. As the battery delivers power, sodium atoms within the anode release electrons (e⁻) and become Na⁺ ions:

Anode (Oxidation):

Na → Na⁺ + e⁻

These electrons travel through the external circuit to power devices, while the Na⁺ ions move through the liquid or solid electrolyte toward the cathode. At the cathode—typically composed of layered transition metal oxides (e.g., NaₓMO₂, where M = Mn, Fe, Ni, etc.), polyanionic compounds, or Prussian blue analogs—reduction takes place as Na⁺ ions and incoming electrons are incorporated into the crystal lattice:

Cathode (Reduction):

Na⁺ + e⁻ + Host → Na–Host

This insertion stabilizes the cathode structure and completes the electrochemical circuit. The voltage generated during discharge depends on the difference in electrochemical potential between the anode and cathode materials, typically ranging from 2.5 to 3.7 volts for commercial Na-ion cells.

During charging, an external voltage greater than the cell’s open-circuit voltage is applied, reversing the electrochemical reactions. Sodium ions are extracted from the cathode through oxidation:

Cathode (Oxidation):

Na–Host → Na⁺ + e⁻ + Host

The released Na⁺ ions traverse the electrolyte back to the anode, while electrons return via the external power source. At the anode, reduction occurs as Na⁺ ions combine with electrons and re-intercalate into the carbon matrix:

Anode (Reduction):

Na⁺ + e⁻ → Na (intercalated)

This process restores the battery’s stored energy, preparing it for the next discharge cycle. Efficient charge transfer, minimal side reactions, and structural stability of electrode materials are critical to achieving long cycle life and high Coulombic efficiency—key metrics for commercial viability.

The electrolyte—usually a sodium salt (e.g., NaClO₄ or NaPF₆) dissolved in organic carbonate solvents—plays a pivotal role in enabling rapid ion transport while maintaining electrochemical stability. During the initial charge cycles, a solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) forms on the anode surface. This passivation layer prevents further electrolyte decomposition while allowing Na⁺ ions to pass through—a delicate balance essential for safety and longevity.

Sodium’s natural abundance (over 1,000 times more prevalent than lithium in Earth’s crust) translates to lower material costs and reduced geopolitical supply risks. Additionally, aluminum can be used as the current collector for the anode in Na-ion batteries (unlike Li-ion, which requires copper), further cutting costs and weight. However, sodium ions are larger and heavier than lithium ions, resulting in slightly lower energy density and slower diffusion kinetics. Ongoing research focuses on developing advanced electrode architectures, nanostructured materials, and solid-state electrolytes to overcome these limitations.

The charge and discharge mechanisms of sodium-ion batteries exemplify the elegant synergy between materials science and electrochemistry, laying a solid foundation for next-generation energy storage. Unlike lithium-ion counterparts, their reliance on abundant, low-cost sodium not only mitigates supply chain risks but also aligns with global sustainability goals. As researchers continuously refine electrode compositions—enhancing stability and energy density—optimize electrolyte formulations to boost cycle life and safety, and advance large-scale manufacturing processes to lower production costs, sodium-ion technology is steadily overcoming remaining technical barriers. This progress positions Na-ion batteries to play a transformative role in decarbonizing energy systems worldwide, from grid-scale storage supporting renewable energy integration to portable power and low-speed electric mobility. By harnessing the simple yet powerful motion of sodium ions, we are not just storing electricity efficiently and affordably—we are forging a more accessible, resilient, and sustainable energy future. It bridges the gap between technological innovation and real-world application, offering a viable path to reduce carbon emissions and build a greener global energy ecosystem.